The Kent State Massacre and America’s Response

On May 4, 1970 on the campus of Kent State University, in Kent, Ohio, four Kent State students were shot to death by members of the Ohio National Guard. The Guardsmen were on campus to disrupt student protests against the war in Vietnam, and to prevent damage to campus property. That sunny May day, thirteen students in total were shot by the guardsmen within a span of less than 13 seconds. The guardsmen fired over sixty bullets into a crowd of protestors, onlookers and bystanders during that brief period of time, killing four and wounding nine. All thirteen of the people shot that day were Kent State students, and of the four killed only two were participating in the protest. The other two were simply walking to class when they were shot and killed. The Ohio National Guard claimed the troops were defending themselves, and no Guardsmen were ever convicted of any crime resulting from the shooting. However, the evidence available suggests that Kent State was something more than self-defense. Kent State was a massacre of US citizens by US armed forces. But, this paper isn’t solely about the shooting that occurred on Kent State’s campus commons that spring day. Instead, this paper analyzes America’s different reactions to the shooting, especially by the media, and argues that the same ideological split that occurred between protestors and the establishment prior to the shooting can be seen in American society’s response to the Kent State massacre.

The events that unfolded on Kent State’s campus on Monday, May 4, 1970 were the culmination of four days of disturbances around the city of Kent and the University campus. Friday, May 1, saw an impromptu and roughly organized gathering of students, activists and agitators outside of some bars in downtown Kent. A few windows were smashed, multiple small fires were set in the streets, and several passing cars were attacked with rocks and small objects thrown by the crowd. The next evening, on Saturday, May 2, a group of protestors gathered on the Kent State campus, and ultimately the school’s ROTC building was burned to the ground. It was that evening that the Ohio National Guard arrived on the campus, having been earlier called in by the Governor of Ohio James Rhodes. Sunday, May 3, was largely uneventful with the soldiers taking position around the burned out ROTC building, and activist students peacefully opposing them close by. It was at this standoff between soldiers and students that one of the students who would later be killed in the Guardsmen’s shooting, Allison Krause, noticed a flower in the barrel of a Guardsman’s rifle and said: “flowers are better then bullets.” Sunday evening students protested at various spots around campus and were repeatedly dispersed by teargas-wielding Guardsmen. The events of Sunday evening foreshadowed what would take place at noon the following day. Unfortunately, the events that would unfold on Monday afternoon would have a tragically fatal ending.

It is easy to connect the May 4 shooting to the series of events that took place in Kent starting on Monday, May 1, but it is also necessary to look further back then the start of that weekend to put Kent in its proper context. Student protests against the Vietnam War had been occurring for years. In fact, as early as 1967 students had taken over administration buildings at the University of Chicago, and at the University of Wisconsin students had held large protests that resulted in multiple reports of police brutality. But, during the latter part of 1969 and into 1970 the large scale student protests had been dwindling due to President Richard Nixon’s pledge to bring troops home, and his policy of Vietnamization, through which US troops were training then handing over the war to the South Vietnamese Army. A close look at several editions of the “underground” newspaper Berkley Barb prior to the May 4 shooting lend credibility to the idea that anti-war protests were slowing down. As the Barb newspapers show, protests themselves had not stopped on campuses they just shifted focus from protests against the war to other issues facing students and the nation. For example, the January 30 – Feb 5, 1970 issue has articles about civil rights events (especially concerning the Black Panthers), students’ rights, healthy living and conservancy. The issue is lined with headlines like “Pickets Vamp on $eal Bloodbath,” and “Union Backs GayLib,” as well as a comic strip entitled “white makes right,” which shows police killing blacks and then receiving medals for it. There is hardly a mention of the war in the edition, and the next edition released one week later, only addressed the war with one large picture on the inside of the cover and a headline that read “Hold US War Criminals Accountable.” The edition published the week prior to the Kent State massacre hardly mentions the war at all, instead focusing on police brutality, the counterculture and students displeasure with ROTC training programs operating on campus grounds. Major headlines from that edition include “Uncle Tim’s OM Orgy,” and “Smogless Saturday.” Clearly, the major issues being taken up by students in early 1970 had more to do with civil rights and conservancy then anti-war movements. It is important at this point to note that the protests that occurred on May 4 and the 3 days prior were without a doubt anti-war protests. So, what caused students to shift their focus away from Woodstock, Tim Leary, Earth Day and the Black Panthers, and back to Vietnam? The answer, Cambodia.

On April 30, 1970 President Nixon announced that the US would not be winding down the war just yet. In fact, it would be expanding the Vietnam War by invading Cambodia. This announcement sent shock waves through the anti-war community and re energized those who had been lulled into passivity by Nixon’s false statements about ending the war.

Once the environment that lead to the May 4 protest is understood it is necessary to consider why this protest, after years of ant-war rallies on campuses and cities around the nation, resulted in a branch of the US military firing at and killing American citizens. There had been tensions between anti-war protestors and authorities at most rallies, and there had been numerous incidents of violence and arrests prior to Kent State, but nothing like what would occur on May 4. Perhaps the shooting was inevitable - somewhere someone was going to get killed for standing up for peace. But, it also seems likely that the attitudes and statements of some powerful figures helped to create a mindset among authorities that the protestors had it coming. Take for instance California Governor Ronald Reagan who is quoted in the LA Times in early April as saying “if it’s to be a bloodbath, let it be now. Appeasement is not the answer.” Less than a month later an even more influential voice would share a similar sentiment when on May 1 President Nixon referred to protestors as “these bums blowing up campuses.” As Peter Hamill wrote in his New York Post column (which was later turned into a spoken word LP) “When you call campus dissenters bums as Nixon did the other day you should not be surprised when they are shot through the head by National Guardsmen.” It was one thing for authority figures to disagree with protestors and even to enforce laws by arresting peaceful protestors, but it was quite another thing to be speaking of American citizens in a way that devalued not only their ideas but their lives. The word bum in particular had an especially negative connotation that equated protestors with worthlessness.

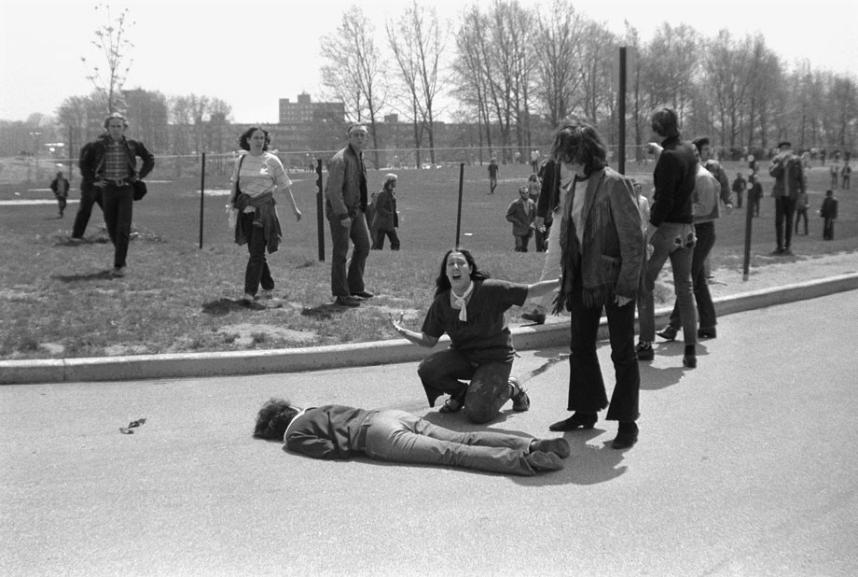

Immediately following the shooting, the Nation’s mainstream press was rife with inaccurate information about what occurred, and their reporting on the shooting seems to indirectly explain that the Guardsmen acted appropriately and that the death of the students, while unfortunate, was largely of their own making. It is important here to remember that two of the students killed were not even participating in the protests, but simply walking to class. Consider the New York Time’s first article about the shooting, which was written by a journalist on the scene at the time of the shooting. The article took up much of the front page, and was accompanied by John Filo’s famous photograph of Jeffrey Miller’s lifeless body lying face first on the concrete, blood dripping from his head, and a young 14 year old runaway from Florida, Mary Vecchio, kneeling over his body with her arms outstretched and her face contorted with sorrow and disbelief (fig. 1). Filo’s photograph was featured on newspaper covers across the nation, and became one of the most iconic images of protests in America. The headline of the New York Times article read “4 Kent State Students Killed by Troops,” and the sub headline was “8 Hurt as Shooting Follows Reported Sniping at Rally.” There are a few problems with those headlines; first 9 students not 8 were hurt (in addition to the four killed), and there was no sniper fire. Other papers also had errors in the stories they ran the day after the massacre occurred, such as The Plain Dealer which listed “10 Hurt at Kent State,” and The Daily Illini reported “12 others injured” besides the four killed. The author of the New York Times piece goes on to write that, to him, the shooting lasted “perhaps a full minute or a little longer.” In reality, the shooting lasted less than fifteen seconds. While the author of the article admitted that he “did not see any indication of sniper fire, nor was the sound of any gunfire audible before the guards volley,” the article itself lent significant credibility to the sniper theory by interviewing several authority figures who pushed the existence of a sniper. The article paraphrases Sylvester Del Corso, Adjunct General to the Ohio National Guard, as stating the guardsmen had been forced to shoot into the crowd after a sniper opened fire against the troops from a nearby rooftop, and the crowd began to move to encircle the guardsmen. Also, directly quoted in the article is Frederick P. Wenger, the Assistant Adjunct General, who backs up the sniper story, saying, “they were under standing orders to take cover and return fire.” The article goes on to use quotes from President Nixon and General Robert Canterbury to seemingly cast blame on the student protestors. President Nixon is quoted as warning “this should remind us all once again that when dissent turns to violence it invites tragedy,” and Canterbury as recollecting that “a crowd of about 600 students had surrounded a unit of about 100 Guardsmen on 3 sides and were throwing rocks at the troops.” Both of these quotes indicate that the students were the ones who initiated the violence, and that the Guardsmen were only protecting themselves. One thing missing from the article, besides truth, is any perspective from student leaders or anyone involved in the anti-war movement. It also does little to connect the protest on campus to the bigger picture regarding anti-war protests across the nation. It almost seems from reading the New York Times article that the shooting at Kent State was an isolated incident, and not part of an anti-war movement that had been raging on and off for the better part of four years.

In comparison, underground newspaper such as the Berkeley Barb and Georgia Straight were quick to discuss the shooting in connection to past anti-war events, and instances of police brutality in America. They also focused much more on the 4 individuals killed at Kent State, and poked fun at President Nixon’s inflammatory remarks. Posters calling for protests against the war in Vietnam, and in remembrance of the Kent State victims, were distributed at colleges across the nation. One such poster distributed at New York University called for a demonstration to “Protest the Kent State Massacre,” on May 8th at 4:30pm. Coincidently, also on May 8th, the Canadian underground newspaper Georgia Straight released its first edition after the Kent State massacre. Front and center was a large printing of the John Filo photograph that was ran by the New York Times in their May 5 edition, and above the photo was the headline “4 “Bums” Killed at Kent,” a direct reference to Nixon’s inflammatory remarks made just days earlier. The main article actually recaps Nixon’s attitude immediately before and after the events by quoting not only his May 1 bum reference, but also his May 5 reminder that when protestors act violently they are inviting tragedy. The Berkeley Barb in their first edition after the massacre ran, on its cover, a giant picture of a riot masked police officer wielding a nightstick in one hand, a revolver in the other, and standing straddled over the listless body of what looks to be a young civilian. The headline reads, or actually seems to plead, “RISE UP ANGRY!!! NO MORE LYING DOWN.” The article which begins on the cover of the newspaper and continues on the inside expresses its exasperation with the state of police violence against mostly peaceful students and protestors. It ties the deaths at Kent State to the 1969 murder of student James Rector, and several “black students in North Carolina,” and lamented that nothing meaningful came out of the previous deaths while wondering if this time would be any different.

One of the most personal and powerful ways in which America responded to the Kent State massacre was through music. Several of the big bands of the day came out with songs remembering the Kent State victims, and there were plenty of obscure artists who paid tribute as well. There is even one rather bizarre song that attempts to portray the events from the Guardsmen’s perspective. Likely, the most well-known and popular Kent State song was also the first one to hit the airwaves. Ohio, written by Neil Young and performed by the band Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young was released less than a month after the shooting. Widely renowned for its simple but profound lyrics like, “Tin soldiers and Nixon coming, we’re finally on our own. This summer I hear the drumming, Four dead in Ohio,” the song was quickly banned from AM radio stations for its seemingly accusatory line about President Nixon. Young is said to have been influenced by photos of the massacre taken by Howard Ruffner, who took over a hundred photographs chronicling the Kent State shooting, and published in Life Magazine immediately after the shooting (fig 2). CSN&Y took a considerable risk releasing the rushed and potentially controversial song even while they had another recently released single currently climbing the charts. The song’s pointed message was different from what CSN&Y were known for, but the risk paid off as the song was quickly recognized as one of the bands most powerful works. Two other popular bands released songs reflecting on the Kent State massacre within a year of it occurring. The Steve Miller Band released Jackson-Kent Blues and the Beach Boy’s released Student Demonstration Time. Interestingly, the Beach Boys version seemed to almost warn against further protests with lyrics like “I know were all fed up with useless wars and racial strife but next time there’s a riot going on, well, you best stay out of sight.” Two, perhaps, less famous woman singers released powerful songs about the massacre as well. Barbara Dane’s The Kent State Massacre, and Ruth Warrick’s 41,000 + 4 both seemed to emphasize the peacefulness of the protests while also connecting the shootings to broader anti-war sentiments. Barbara Dane’s song emphasized the peacefulness of the protests with lyrics like: “the air was full of springtime, the flowers were in bloom […] young students stood with empty hands to face the bayonets.” Some more of her lyrics said the students “marched and sang a peaceful song,” while “they laughed and joked with troops, and some of them did say: we march to bring the GIs home, and we are not afraid.” Talking about the moment of the shooting, Dane sings: “no warning were they given, no mercy and no chance.” Mrs. Warrick’s ballad connects the shooting to broader anti-war sentiments with lyrics like: “41,000 lie dead from this war, plus four from the massacre at Kent, a sad score killing, senseless killing, destruction and shame, can our country ever redeem its good name.” She also insinuates that a powerful few are pulling the government’s strings, “greedy war breeders are washed with the blood of the students, power back to the people […] time for Congress to take back its rights.” One group that takes a different approach with their song Knife is the band Genesis. The song is written from the perspective of Guardsmen and their lyrics are rather chilling, “some of you are going to die – martyrs of course to the freedom that I shall provide.” Genesis’ lyrics, as blunt as they may be, were representative of the Americans that sided with the notion that the Guardsmen were just doing their jobs. Most of the songs made about Kent State are rather obscure, but Ohio received mainstream popularity, and is still a regular on classic rock stations.

A year after the massacre had taken place the nation was still coming to grips with the shooting. There were still numerous court cases that would take place, attempting to determine who was responsible, and there was a fierce debate raging about the best ways to commemorate the shooting. One magazine article in particular does a good job of putting this debate in context, and discussing how the nation should remember the event and its victims. Joe Eszterhas, wrote an article for Rolling Stone magazine in June of 1971 that discussed the 1 year memorial for the Kent State victims held at Kent State University on May 4, 1971, and the attitude of the nation at large in regards to the shootings. In describing the scene at the memorial Eszterhas writes:

The University president, Robert I. White, who was having a martini when the shots rang out last year; sits a few feet down from the gleaming wheelchair [belonging to one of the students injured in the shooting], looking uncomfortable. Four sets of parents, their lifestyles altered, their flag-decal belief in America buried in four separate cemeteries across the land – Allison, Jeff, Sandy and Bill, lives between dashes set on grave markers – are away from the campus today because Robert I. White did not think it would be “beneficial” to invite them to the ceremonies marking the death of their four children.

Clearly Eszterhas is not a fan of how the University, and Mr. White in particular, handled the memorial, but the article’s author is also attempting to reflect a divided nation. On one side is the Kent State president, a model of conservative authority, deciding what an appropriate memorial is for the slain students, and on the other side are the four sets of parents who, prohibited from memorializing their children on the campus where they were murdered, and largely ignored by American society, were forced to the sidelines on a day where they should be central and key figures. In the mainstream press immediately after the shooting there was little discussion about the actual students that were hurt or killed. Eszterhas’s article draws a sort of parallel to that by showing how the University is marginalizing the individuals who lost their lives by making the memorial as uncontroversial as possible. Also, by prohibiting the parents from attending, the University gave credence to the notion that the students were somehow to blame for their deaths.

Conversely, mainstream newspapers covered the 1 year anniversary a bit differently. In the New York Time’s May 4, 1970 edition the only mention that the parents were barred from attending the memorial on campus is a short, indirect, blurb at the end of an article about the memorial that says only “student and faculty members” are allowed to attend. That same article opens with a quote from a sophomore at Kent State talking about how the shooting should be remembered on campus, “quiet, not loud, that’s the way it should be. People go to the candlelight vigil and then go back to their own thing.” The Time’s writer goes on to paraphrase the student as saying the event should be “silent, private, nonpolitical and then back to classes.” The article fails to mention the names of any of the slain students, and ignores the wounded entirely. There is also little background explaining the shootings other than a brief mention that it occurred during an “anti-war demonstration.” On May 5, 1971 the New York Times published another article that described the memorial event in a bit more detail, and included a short mention of the peaceful sit-in that occurred after the memorial. But, the article didn’t mention anything about the parents of the slain students, or that certain student groups were unhappy with the memorial.

The grief and devastation that was brought onto the parents of the dead students didn’t end with the burials of their children. The parents were forced to watch a divided nation very publicly debate the guilt of all involved. More often than not the verdict came somewhere between, the students had it coming, and the Guardsmen should have shot more of them, but there was also a significant portion of people that thought the Guardsmen’s behavior was criminal. Leading up to the 1 year anniversary of the shooting, the parents of one of the slain students, Allison Krause, attempted to have a short message printed in newspapers around the country. The note was simple and to the point: “this is in memory of Allison, who was shot to death a year ago at Kent State by National Guardsmen.” Unfortunately, some papers wouldn’t print the ad. Here is the conversation between The Washington Post and representatives from the Krause family:

“It is not the policy of the Post to publish ads that are defamatory”

“Of what?”

“Of the National Guard.”

“It has clearly been established that she was shot by the guard, established by the FBI, by the president’s commission.”

”It obviously hasn’t been established, because no Guardsmen has been indicted.”

Another newspaper, The St. Louis Post-Dispatch agreed to run the message, but never did. The reason they gave to the family: “somebody in the composing room had thrown it out.” The behavior of the newspapers reflects the mainstream media’s reluctance to be seen siding with the anti-establishment movements, regardless of how minor of a statement their actions may have made. Posting the Krause family’s message certainly would not have meant that a particular newspaper held the Guardsmen responsible, but to the newspapers it was more important to be seen in solidarity with “America” then to help a couple of American’s deal with their grief.

Looking at the various responses to the Kent State shooting it appears clear that the nation was decidedly split in regards to who it held accountable for the shooting, and to deeper questions about the direction of American society in particular. Leading up to the shooting, figures of authority like Governor Ronald Reagan and President Nixon were publicly denouncing the protestors, and using dangerously provocative words to denounce them and their actions. Immediately after the shooting, the New York Times quoted President Nixon as he declared that “tragedy” is what occurs when protestors turn “to violence.” His remarks coupled with ones made by other authority figures such as General Del Corso seemed to insinuate that the Guardsmen’s reaction was one that was forced onto them by a dangerous student body. The mainstream newspapers, such as the New York Times, also had considerable errors regarding the events of the shooting in their immediate printings. Many misreported the number of injured students, and gave credibility to the notion that the Guardsmen were just returning fire from a hostile sniper. Meanwhile, the reaction underground newspapers, such as the Berkley Barb and Georgia Straight, had was radically different. The Barb listed several instances of police brutality and asked will Kent State be any different in terms of prompting meaningful change, and Georgia Straight mocked Nixon’s crass statements. It was through the photographs of Jon Filo and Howard Ruffner that the nation saw firsthand what occurred at Kent State, and while there isn’t anything reflective of differences among society noticeable in the pictures themselves they certainly evoked different responses from the people who viewed them. Take, for instance, the musician Neil Young. It was Ruffner’s pictures in Life magazine that motivated Young to write one of the most famous protests songs ever, Ohio. It is not clear what motivated the band Genesis to write their song Knife, which represented the shootings through the perspective of Guardsmen, but their reaction to the shooting was decidedly different than that of Neil Young. Music served as an important conduit for Americans to express their feelings about the shootings. Barbara Dane and Ruth Warrick sung about the victim’s youthful innocence, while the Beach Boy’s sang a warning of sorts to would be protestors. Perhaps one event that typified the type of differences in society’s response to Kent State is the 1 year anniversary of the shooting, which was held on the campus and organized mostly by school administrators. In a moment of callousness the president of Kent State chose to bar the Parents of the slain students from attending the event. In covering the memorial at Kent State, the NY Times chose to not even mention the parents, while the Rolling Stone’s coverage not only mentioned the parents, and exclaimed its rage at their exclusion, it detailed some of the horrors the parents were facing in dealing with their tragedy.

Incredibly, the issues that were dividing the nation prior to the shooting couldn’t even be bridged by the public massacre of four young Americans; that their killers were wearing US military uniforms may have played a part in that. America responded in many ways to the shooting, and while most thought it a real tragedy, many weren’t quite sure why it occurred or who was to blame. For people who relied only on the mainstream news or the underground newspapers to learn about what happened at Kent State it would have been difficult to truly understand what occurred before and during the shooting. The mainstream newspapers fueled the assumption that the protestors had gotten violent, and the Guardsmen, acting defensively, had restored law and order. But, that only paints a partial picture. In many ways the reporting by the underground papers was more forthcoming about the Guardsmen’s actions, but they too had an agenda based on the audience they were hoping to sell papers to. In their articles the protestors did no wrong. The truth is somewhere in between. The tragedy shouldn’t have occurred, and whether or not it was bound to happen somewhere is debatable, but the ideological split that can be seen in America’s response to the shooting was representative of the differences between the protestors on campus and the authority figures trying to stop their dissent. Those ideological differences divided families, students and the nation in general. Tragically, they also led to the deaths of four young American students at the hands of the Ohio National Guard.

Keegan F. Labrador

April 13, 2015

Works Cited

Primary Sources:

• The Berkeley Barb, January 30, 1970.

• The Berkeley Barb, February 06, 1970.

• The Berkeley Barb, April 24, 1970.

• LA Times, April 8th, 1970

• Georgia Straight, May 8th, 1970

• The Plain Dealer, May 5th, 1970

• The Daily Illini, May 5th, 1970

• NY Times, May 5th, 1970.

• NY Times, May 4th, 1971.

• NY Times, May 5th, 1971.

• The Berkeley Barb, May 8th, 1970.

• Eszterhas, Joe. "Ohio Honors Its Dead." The Rolling Stones, June 1, 1971.

• http://www.library.kent.edu/howard-ruffner-papers-and-photographs-1970-71

• http://hruffnerimages.com/ • Barbra Dane, I Hate the Capitalist System, The Kent State Massacre, 1973, Paredon Records

• Ruth Warrick, 41,000 plus 4 (Ballad of the Kent State Massacre), 1971, Ruth Warrick Enterprises • Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Ohio, 1970, Atlantic Records

• Genesis, The Knife, 1971, Charisma/Virgin Records

Secondary Sources:

• Gordon, William A. The Fourth of May: Killings and Cover-ups at Kent State. Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1990.

• "Vietnam War: Kent / Jackson State Songs." - Rate Your Music. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://rateyourmusic.com/list/JBrummer/vietnam_war__kent___jackson_state_songs/

• http://www.nyu.edu/library/bobst/collections/exhibits/arch/1970/1970-2.html

• "The History of 'Ohio': Crosby Stills, Nash & Young's Raw Reminder of the Kent State Massacre." Ultimate Classic Rock. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://ultimateclassicrock.com/csny-ohio/.

• Anderson, Terry H. The Sixties. New York: Longman, 1999.

• CNN. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/COMMUNITY/transcripts/2000/5/4/filo/.

• CNN. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0005/04/tod.05.html.

• "The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum." The Story of "Ohio" Accessed April 6, 2015. http://rockhall.com/blog/post/crosby-stills-nash-young-ohio-kent-state-shooting/.